Tracking the Silk Road mastermind

This story has been updated to correct the title of Jared Der-Yeghiayan, a Homeland Security Investigations special agent.

NEW YORK – When federal agents arrested Ross William Ulbricht, they announced they'd captured the mastermind behind Silk Road, the Dark Web marketplace that trafficked in millions of dollars in illegal drugs and other illicit transactions.

But did they?

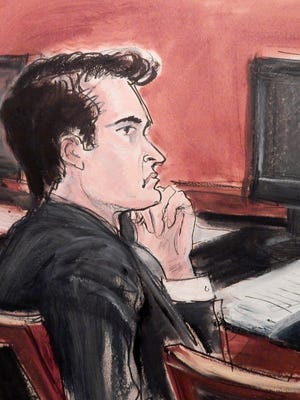

The question shadows the 15th floor Manhattan federal courtroom where Ulbricht, 30, went on trial this week on charges that could put him behind bars for the rest of his life.

The initial prosecution witness told a jury of six women and six men details from two years of computer investigation, undercover work and subterfuge that culminated in Ulbricht's Oct. 2013 arrest inside a San Francisco public library.

Jared Der-Yeghiayan, a Homeland Security Investigations special agent, also sketched the inner workings of Silk Road, describing it as a booming eBay of the underworld where more than $200 million in heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines and phony identifications were bought and sold.

Additionally, Der-Yeghiayan provided first-hand details of Ulbricht's capture, which prosecutors say produced definitive evidence he was the Dread Pirate Roberts, the nom de Net used by Silk Road's creator and director.

Challenging that allegation, defense lawyer Joshua Dratel said Ulbricht launched Silk Road as an "economic experiment," but quickly passed control to others who later set up the founder as a "fall guy." He argued that Dread Pirate Roberts could have been another man once suspected by government investigators but never charged in the case.

Amid the clashing arguments in the darknet whodunit, Ulbricht has repeatedly flashed regular what-me-worry smiles and thumbs up signs to family and friends in the courtroom.

Ulbricht planned Silk Road as far back as 2009, Assistant U.S. Attorney Timothy Howard told jurors. But, living in Austin, Texas with his family at the time, Ulbricht had no large cache of drugs. So he rented a nearby cabin, started raising hallucinogenic mushrooms, and began advertising them for sale, Howard alleged.

By 2011, Silk Road was open for business, with secrecy measures designed to make it difficult for investigators to identify the marketplace's operator, buyers and sellers. The business used a computer routing system known as Tor that sent messages from the participants through multiple computer servers located overseas and rented under false identities.

Silk Road required its anonymous buyers to trade money for bitcoins and then use the electronic currency to make purchases. The marketplace charged 10% to 12% fee on each transaction, generating a bitcoin stash for Ulbricht that prosecutors said was worth roughly $18 million at the time of his arrest.

Drug sellers were instructed to to "creatively disguise" the packages they mailed to buyers.

"Make sure the exterior of the package raises no suspicion," stated one protocol shown to jurors. All packages that might have a scent that could draw attention from government dogs trained to sniff out drugs should be "vacuum sealed," another instruction stressed.

But the preparations, markedly more efficient than some drugs-by-mail transactions, themselves attracted special scrutiny.

Der-Yeghiayan, who was based at Chicago O'Hare International Airport, testified that a colleague in September 2011 showed him unusual packages found during inspections of mail passing through the air hub from the Netherlands.

Each package contained envelopes containing pills of Ecstasy, a synthetic drug similar to methamphetamine. The pills were in zip-locked plastic bags that themselves were inside vacuum-sealed silver foil. During the next few months, other inspections at O'Hare turned up what Der-Yeghiayan called "commercialized" mail packages containing heroin, cocaine, LSD and other illegal drugs.

"It looked like they went rough unusual steps to mask it, hide it from detection," the investigator testified, adding that the shipments sent O'Hare drug seizures spiking higher, month by month.

Der-Yeghiayan said he and other agents investigators linked many of the seizures to Silk Road vendors, in part because descriptions of the offerings hawked on the online bazaar matched the originating countries, drugs and pill markings found in packages plucked from through the mail flowing through at O'Hare.

Investigators decided to gather evidence against Silk Road and its participants by making undercover drug buys. Der-Heghiayan testified that agents wired $7,000 in April 2013 to obtain 27.27 bitcoins from the Mt. Gox exchange, at the time the world's largest trading market for the digital currency.

Then, using the pseudonym "dripsofacid," the investigators logged into Silk Road and ordered 1,000 Ecstasy pills from a Germany-based seller identified as "SuperTrips" for the bitcoin equivalent of nearly $5,500 that they transferred to the marketplace. The drugs were shipped to a Chicago postal box investigators had established under a false name.

Working undercover, Der-Yeghiayan simultaneously used a variety of online pseudonyms to contact other Silk Road participants. He convinced one person known in Silk Road chats as "Scout" to become a cooperating witness and let him assume control of her online identity.

The breakthrough got Der-Yeghiayan inside the alleged criminal enterprise with an already-approved security identifier code. The development enabled him to join a small crew of moderators who assisted Dread Pirate Roberts by managing Silk Road's online user forums and answering questions from buyers and sellers. According to the agent's testimony, neither the moderators nor marketplace mastermind ever met face-to-face.

Operating under the new online name "Cirrus," Der-Yeghiayan regularly worked ten-to-twelve-hour days moderating Silk Road forums for roughly $1,000 in bitcoins. Federal agents transferred the funds off the site, converted it to U.S. currency, then held the payments as investigation evidence.

Of even greater significance, the agent also participated in direct online communications with Dread Pirate Roberts, who exchanged work messages with the Silk Road workers via a secure staff chat system.

While Der-Yeghiayan worked inside, court evidence not yet introduced to the jury shows that other federal investigators tried to identify the mastermind.

In July 2013, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents intercepted a package in mail entering the U.S. from Canada. Inside were fake driver's licenses with Ulbricht's photograph but different names that appeared to have been issued by government agencies from several U.S. states, Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia.

A Homeland Security agent performed a controlled delivery of the phony licenses to Ulbricht at the San Francisco home where he was renting a room under the alias "Josh," the court records show. Ulbricht produced a copy of his authentic Texas-issued driver's license, but allegedly told the agent little more.

However, the incident established that Ulbricht lived near San Francisco's Cafe Bello, located in an area where federal court records show a computer user had logged into a server that was used to administer Silk Road. Der-Yeghiayan testified that he and other investigators gathered nearby On Sept. 30, 2013.

The following day, Der-Yeghiayan said undercover investigators watched as Ulbricht went into Cafe Bello, found it too crowded, and then went into the science fiction section of the library branch next door. Already online at Silk Road as Cirrus in his moderator role, the agent waited until his laptop screen showed Dread Pirate Roberts had just logged in.

Cirrus contacted the mastermind, and asked him to check a recent posting by a Silk Road participant. Complying, the unsuspecting mastermind typed back a question: "ok, which post?"

The question meant Silk Road's operator was now logged into the online marketplace under the Dread Pirate Roberts pseudonym. Der-Yeghiayan notified fellow agents who had taken up positions near Ulbricht in the library. They quickly moved in, grabbing Ulbricht's laptop before he could close it or log off, pressing him against a large glass window and arresting him.

Investigation photographs displayed to jurors showed that the chat exchange still in place on Ulbricht's computer screen matched the one on Der-Yeghiayan's laptop. The agent testified that investigators determined that Internet pages Ulbricht visited shortly before the fateful chat included administration-level sites for Silk Road.

Moreover, Ulbricht was logged in under the unique Silk Road security code of Dread Pirate Roberts, Der-Yeghiayan testified.

But, cross-examined by Ulbricht attorney Dratel, the agent acknowledged that the security code was essentially the online equivalent of a key that could be used by others. "There could be multiple copies of a private key that people could have," Der-Yeghiayan testified.

Drawing on evidence provided to the defense team, Dratel asked Der-Yeghiayan if there were times during the investigation when federal agents were unsure whether more than one person took on the Dread Pirate Roberts persona.

"There were times when there were writings that made me think it was another person," said Der-Yeghiayan.

Answering other defense questions, the agent also testified that he and other investigators once suspected Dread Pirate Roberts could be Mark Karpeles, the former CEO of the now defunct Mt. Gox bitcoin exchange.

"This is probably going to be disappointing for you, but I am not and have never been Dread Pirate Roberts," Karpeles said in written responses afterward. "I have nothing to do with Silk Road and do not condone what has been happening there."

U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest adjourned the trial for the Martin Luther King Day holiday weekend to consider arguments on how far she'll permit Dratel to pursue the someone-else-did-it strategy.

Who's on firmer ground, the prosecution or defense?

Nicolas Christin, an assistant research professor in electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, said the corroborating evidence government investigators obtained from Ulbricht's computer only goes so far.

"What it does show is that Mr. Ulbricht had access to the (Silk Road) administrative accounts," said Christin. "What it does not show is that he was not necessarily the only one who had the keys to the kingdom, so to speak, or how long he had that access. That's a lot harder to show"

As for argument by Ulbricht's defense team, Christin said "they are trying to raise reasonable doubts. We'll see how that pans out with the jury."